[Zulu]: "Materialism & Empiriocriticism" had one and only one objective, and it was purely political: to lump A. Bogdanov together with Mach and thus denigrate him to the point of slander to undermine his popularity within the Party (which had nothing to do with Mach). It was Lenin's gravest mistake. Treating it as some kind of a profound study in philosophy is ridiculous. Why this was done by the priests of the Marxist parish in the USSR is understandable, why it is kept being done by some people in the 21st century is not...

[P. Cockshott]: Are you expressing an opinion in support of Mach or of Bogdanov?

[Zulu]: Bogdanov, of course. Except it's not an opinion, but a fact. I mean, the nature of that Lenin's work as a political attack on a fellow Bolshevik. A matter of opinion would be whether that attack and the chosen path of attack was really necessitated and justified or not. And as much as I love Granpa Lenin with all my heart for all that he did, in my opinion, the particular affair in question was completely unnecessary and unjustified, damn fucking shame and a debacle.

[John Lowrie]: I agree. Bogdanov was not the subjectivist of Lenin's caricature but a decided objectivist. Thus he states, "The objective character of the physical world consists in the fact that it exists not for me personally, but for all... the objectivity of the physical series - this is its universal validity". On the other hand, subjective experience was that which lacked universal validity". Incidentally, Bogdanov was arrested the night of 8th September 1923 and put in the Lubyanka prison. So much for those who hold that the degeneration of the revolution was all Stalin's doing! Bogdanov, who despised Plekhanov's "universal philosophy" of dialectical materialism, protested against Plekhanov's alluding to him as a Machist.

The irony is all the greater, for Lenin ensured that Bogdanov's writings were given little exposure, while later Stalin turned Lenin into figure of papal infallibility and Bogdanov was excommunicated from the sacred circle of Leninist orthodoxy. The irony is that at the time Stalin characterised Lenin's "Materialism and Empiriocriticism" as a storm in a teacup and secretly communicated his support to Bogdanov and his group. Even more ironical is Bogdanov's reply to Lenin in ''The Fall of the great Fetish.'' Bogdanov had argued that ''Social being and social consciousness... is identical.'' Lenin contended that this was 'idealism.' Now Bogdanov pointed out that if speech arises as an essential component in the course of the production process, then social being and social consciousness are identical. (Only now are Bogdanov's works being translated into English.)

The irony continues in that in his "Concerning Marxism and Linguistics" of 1948 Stalin reaffirmed Bogdanov's thesis, albeit without acknowledgement. He had already done this with his thesis in ''The Foundations of Leninism''that revolution was likely to occur at the weakest links in the imperialist chain. Stalin attributed this thesis to Lenin, but in fact it was taken from Bogdanov's "Tektology"

[Zulu]: Yeah. The irony is that Bogdanov sort of anticipated all that in his response to "Materialism & Empirio-Criticism". It's called "Faith and Science" and is yet to be translated. There Bogdanov both dissects the work itself, and utilizes it to illustrate the difference between the two modes of thinking. The tendency to seek and proclaim "absolute truths" and the reliance on authority in the arguments characterize Lenin as essentially a religious thinker...

I used to get triggered, when I was but a neophyte, when some people called Marxism a "secular religion". But the facts are there, and after reading Bogdanov I had to admit that "Materialism and Empirio-Criticism" certainly gave the Soviet scholastics a lot to work with. One most egregious example was the crusade against "Einsteinianism" that almost got underway when certain professors, encouraged by the "triumph" of Lysenko over "Morganism-Weismannism", began quotemining it to "prove" all revisions and additions to classical mechanics to be bourgeois idealism. This attempt fell flat on its face rather quickly though, as a bunch of real physicists wrote a letter to L. Beria to the tune of whether he wanted Marxist-Leninist purity or the nuclear bomb. The choice was plain and simple enough.

In general, the relation of Lenin and Bogdanov is a long, sad and didactic story. And it starts with the fact that the former was a lawyer by trade, and the latter was a physician. So, in his "Empiriomonism" Bogdanov set out to supplant the Hegelian mumbo-jumbo of the classical Marxism with something more in line with the contemporary scientific method, which was still under development at the time, so that it could remain up-to-date and what it proclaimed to be - a theory of scientific communism. But Plekhanov and then Lenin said: "No, Hegelian mumbo-jumbo stays in place, because who are we to doubt Marx?"

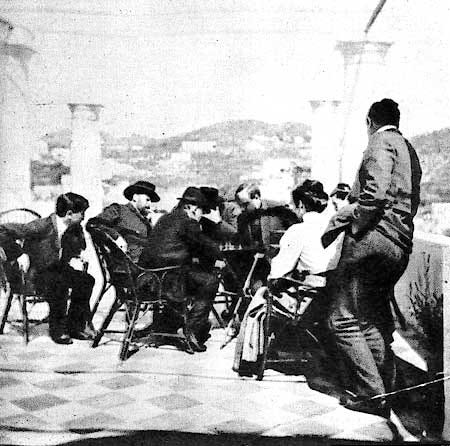

Then, in the aftermath of the Revolution of 1905-07, there was a disagreement about the path the Bolsheviks should take, and most importantly about who gets to control the party funds, and in particular N. Schmidt's inheritance. Next there were a few games of chess between Lenin and Bogdanov, which, according to M. Gorky, Lenin all lost and got real mad about it. So one can't help but suspect that mere pettiness played some part in the subsequent Lenin's drive to marginalize Bogdanov and his close associates (who had their own differences between them). Most of them (Krassin, Lunacharsky, Bazarov) would rejoin the top ranks of the Bolsheviks in 1917, but not Bogdanov, who apparently thought that it would be impossible for him to collaborate with Lenin, so he remained with the "other ranks" (his clandestine moniker from 1905 being "Private", by the way).

That's why I call it a debacle. Bogdanov would have been an invaluable asset to the Party and the young Soviet republic in any position - the higher, the better. But alas, instead of any serious attempt at rapprochement, Lenin chose to be petty to the end and torpedoed another good idea of Bogdanov, namely, the Proletkult...

If only Lenin could find it in himself to be able to accept the fact that Bogdanov was more insightful about some things. The possibilities might have been amazing. They could have made another glorious duo on the pages of history, like Marx & Engels, Castro & Guevara... The saddest part is that even from the rationale that the Bolsheviks needed a single top leader, and Lenin was best suited for this role, he did not really have to have Bogdanov expelled to consolidate that leadership. I mean, he was like almost destined to, because of his brother, who had been executed by the czar. Everybody knew this and was sure that Lenin was going to see this whole revolutionary thing through, would not defect, would not compromise, would not run away with the party funds. That's why he always had all the hardliners firmly behind him, even as Bogdanov's group was pushing for a harder line than himself.

As for Stalin, his relation to Bogdanov was a practical one. Prior and during 1905 Bogdanov was confined by the police to his permanent place of residence, which happened to be the city of Tula, which happened to be the center of small arms manufacturing, so it's up to everyone's imagination what kind of connection there was between him as the main Bolshevik organizer "on the ground" and Stalin, who was basically the chief of the Caucasian pistoleros at the time. In later years, when Stalin was on his way to supreme power, he saw to it that Bogdanov, by then a doubly marginalized suspect of political dissent, received enough funds to get his project of research into blood transfusion going.

How much Bogdanov's theoretical thought influenced Stalin is debatable. Officially, in "The History of VKP(b)" he codified "Materialism and Empirio-Criticism" as the true orthodoxy. He also mentioned "Bogdanovism" rather disparagingly in his "Response to Yaroshenko" in "The Economic Problems of Socialism".

Ironically, back in 1937, when Stalin gave the order to draft a textbook on political economy (which "The Economic Problems" were all about), he instructed the committee that the task was assigned to, to use Bogdanov's "Short Course of Economic Science" from the early 1900s as a starting point (it was also translated into English by the CPGB in the 1920s, by the way).

Stalin used to make notes on the margins of some of the books he read. In total, there are 392 such books and journals preserved in the Russian State Archive. Among those there are 5 different editions of that Bogdanov's textbook, but no other books by him. (Incidentally, the earliest edition contains a stamp signifying that it had previously been in the library of the czarist finance ministry...)

On a final note, I'm also glad about this renewed interest in Bogdanov, which seems to have cropped up in the recent years, although I fully expect that these enthusiasts for Bogdanov's legacy will tend to present this story as though Bogdanov was "a good guy", and Lenin was "a bad guy". This would be wrong, of course, as both were "good guys". But all good guys have their human/monkey flaws, that sometimes lead to regrettable misunderstandings and tragic consequences. One must always keep this in mind.

[John Lowrie]: J. D. White in his "Marx and Russia" (2019) and "The Red Hamlet: the Life and Ideas of Alexander Bogdanov" (2018) examines many of the issues you attest above. One is that when Marx came to study Russian and other social conditions he came to abandon all Hegelian schemes. Thus in his famous letter to Mikhailovsky he complained of him: "That he feels he must absolutely metamorphose my historical sketch of the genesis of capitalism in Western Europe into a historic-philosophical theory of the universal path every people is fated to tread". Bogdanov despised Plekhanov and rejected his universal "philosophy" of dialectical materialism. According to White, Lenin's "Materialism" was written to defend Plekhanov and undermine Bogdanov. Bogdanov held Lenin in his "Materialism" to be pompously posturing with pseudo-erudition ("The Red Hamlet", p. 246).

* * * *

A. BOGDANOV. "Red Star" (1908). Excerpt.

On the one hand, the Terran globe is terribly fragmented by political and national partitions, so that the struggle for communism there is carried out not as a whole united process in a single vast society, but as a number of unique and autonomous processes in separate societies, divided by state systems, language and sometimes race. On the other hand, the forms of social struggle are much more crude and mechanistic, than it was with us, and open material violence plays an incomparably greater part, realized by standing armies and rebellions.

Due to all this it follows, that the problem of social revolution becomes very uncertain. Not one, but multiple social revolutions, in different countries and at different times are to be expected. Even their character will probably not be quite the same, and, most importantly, their outcomes will be dubious and unstable. In some cases, with the support of the army ad high military tech the ruling classes might be able to inflict such a crushing defeat on the rebelling proletariat, that it will throw the cause of communism back for decades in entire vast nations. Examples of this kind have already been recorded in Terran chronicles. Then, those separate advanced countries, in which communism prevails, will be like islands in the midst of the hostile capitalist, and even to some extent pre-capitalist world. Struggling for their dominance, the upper classes of the noncommunist countries will direct all their efforts to destroy these islands. They will regularly organize military invasions of these nations, and will find inside them enough allies from the ranks of former proprietors, large and small, ready for any treason. The result of these clashes is hard to predict. But even where communism holds on and emerges victorious, its character will be for a long time deeply distorted by the many years of the state of siege, the unavoidable terror and militarism with the inevitable consequence of barbaric patriotism. This will be a far cry from our communism.